Cyberpunk is a dystopian futuristic subgenre of science fiction that focuses on a "combination of lowlife and high tech,"[1] juxtaposing futuristic technology and scientific breakthroughs, such as artificial intelligence and cybernetics, with societal breakdown or degradation. [2] Much of cyberpunk can be traced back to the New Wave science fiction movement of the 1960s and 1970s, when authors such as Philip K. Dick, Michael Moorcock, Roger Zelazny, John Brunner, J. G. Ballard, Philip José Farmer, and Harlan Ellison looked at the impact of drug culture, technology, and the sexual revolution while avoiding the utopian tendencies of previous science fiction.

Judge Dredd, first published in 1977, was the first comic book to tackle cyberpunk themes. [3] William Gibson's famous debut novel Neuromancer, published in 1984, helped establish cyberpunk as a genre, drawing inspiration from punk subculture and early hacker culture. Bruce Sterling and Rudy Rucker were two other notable cyberpunk writers. The Japanese cyberpunk subgenre began in 1982 with the publication of Katsuhiro Otomo's manga series Akira, which was later popularised by its 1988 anime film adaptation (also directed by Otomo).

Ridley Scott's Blade Runner, released in 1982, is one of several books by Philip K. Dick that have been turned into films (in this case, Do Androids Dream of Electric Sheep?). Max Headroom, a futuristic dystopia ruled by an oligarchy of television networks, was the "first cyberpunk television series"[4], set in a futuristic dystopia dominated by an oligarchy of television networks, with computer hacking playing a prominent role in several narrative lines. Johnny Mnemonic (1995)[5] and New Rose Hotel (1998), both inspired on short tales by William Gibson, were commercial and critical flops, while The Matrix trilogy (1999–2003) and Judge Dredd (1995) were among the most popular cyberpunk films.

Blade Runner 2049 (2017), a sequel to the 1982 film, as well as Upgrade (2018), Dredd (2012), Alita: Battle Angel (2019) based on the 1990s Japanese manga Battle Angel Alita, the 2018 Netflix TV series Altered Carbon based on Richard K. Morgan's 2002 novel of the same name, the 2020 remake of 1997 role-playing video game Final Fantasy VII, and the video game Cyberpunk 2077 (2020) based on the novel Cyberpunk 2077 (2020

Background

Lawrence Person has sought to describe the cyberpunk literary movement's content and spirit, stating:

Characters in classic cyberpunk stories were marginalised, alienated loners who lived on the outskirts of society in dystopic futures characterised by fast technological development, a pervasive datasphere of electronic information, and invasive human body modification.

[8] Lawrence Person

The fight between artificial intelligences, hackers, and megacorporations is common in cyberpunk narratives, which are usually set in a near-future Earth rather of the far-future settings or planetary vistas found in works like Isaac Asimov's Foundation or Frank Herbert's Dune. [9] The settings are typically post-industrial dystopias, yet they frequently feature exceptional cultural ferment and the use of technology in ways that its founders never imagined ("the street finds its own uses for things"). [10] The mood of the genre is reminiscent of film noir, and literary works in the genre frequently employ detective fiction techniques. [11] According to some accounts, cyberpunk has evolved from a literary movement to a genre of science fiction as a result of the small number of writers and the changeover.

History and origins

This had a huge impact on a new generation of writers, some of whom coined the term "cyberpunk" to describe their movement. Bruce Sterling, one of the participants, later stated:

[Ballard] was a towering figure in the community of American science fiction writers of my generation—cyberpunks, humanists, and so on. We used to have heated debates about who was more Ballardian than the other. We knew we weren't fit to polish the man's boots, and we couldn't fathom how we'd get to a place where we could produce work he'd respect or tolerate, but at least we could see the pinnacle of his achievement. [18]

Following generations saw Ballard, Zelazny, and the rest of New Wave as bringing greater "reality" to science fiction, and they strove to expand on this. [requires citation]

Nova, a 1968 novel by Samuel R. Delany, is also regarded as one of the key forerunners of the cyberpunk movement.

[19] It foreshadows, for example, cyberpunk's standard cliché of human-computer interaction via implants. [20] Delany allegedly influenced writer William Gibson[21], and his novel Neuromancer has allusions to Nova. [requires citation]

The Philip K. Dick novel Do Androids Dream of Electric Sheep, first published in 1968, was similarly influential and widely considered as proto-cyberpunk[by whom?]. It examines ethical and moral problems with cybernetic, artificial intelligence in a way that is more "realist" than the Isaac Asimov Robot series that laid its philosophical foundation. Presenting precisely the general feeling of dystopian post-economic-apocalyptic future as Gibson and Sterling later deliver, it examines ethical and moral problems with cybernetic, artificial intelligence in a way that is more "realist" than the Isaac Asimov Robot series that laid its philosophical foundation. K. W. Jeter, Dick's protege and friend, authored a novel called Dr. Adder in 1972 that, Dick lamented, could have been more significant in the area if it had been published at the time. [requires citation] It wasn't released until 1984, after which Jeter turned it into the first of a trilogy, which included The Glass Hammer.Death Arms (1985) and (1987). Before writing three authorised sequels to Do Androids Dream of Electric Sheep, Jeter wrote several solo cyberpunk novels, including Blade Runner 2: The Edge of Human (1995), Blade Runner 3: Replicant Night (1996), and Blade Runner 4: Eye and Talon.

Do Androids Dream of Electric Sheep was adapted into the landmark 1982 film Blade Runner. This was a year after William Gibson's novella "Johnny Mnemonic" helped to popularise proto-cyberpunk ideas. Another dismal future is depicted in that story, which was eventually adapted into a film in 1995. Human couriers transport computer data stored cybernetically in their own minds.

Style and ethos

William Gibson, Neal Stephenson, Bruce Sterling, Bruce Bethke, Pat Cadigan, Rudy Rucker, and John Shirley are all key figures in the cyberpunk movement. Some view Philip K. Dick (author of Do Androids Dream of Electric Sheep?, which was incorporated into the film Blade Runner) as foreshadowing the movement. [31]

Blade Runner is regarded as a classic example of the cyberpunk aesthetic and subject. [9] Cyberpunk 2020 and Shadowrun, for example, are video games, board games, and tabletop role-playing games with plots largely influenced by cyberpunk fiction and cinema. Some fashion and music fads were dubbed as cyberpunk beginning in the early 1990s. Akira, Ghost in the Shell, and Cowboy Bebop are among the most well-known examples of cyberpunk in anime and manga (Japanese cyberpunk). [32]

Protagonists

Many cyberpunk heroes, like Case, are duped into circumstances in which they have little or no choice, and while they may see things through, they do not necessarily emerge any better off than they were before. The "punk" element of cyberpunk is the emphasis on misfits and malcontents.

Society and government

Cyberpunk can be intended to disquiet readers and call them to action. It often expresses a sense of rebellion, suggesting that one could describe it as a type of cultural revolution in science fiction. In the words of author and critic David Brin:

...a closer examination of [cyberpunk authors] reveals that they almost always depict future civilizations in which governments have become weak and pitiful... Popular science fiction stories like Gibson, Williams, Cadigan, and others do depict Orwellian power grabs in the twenty-first century, but almost usually in the hands of a wealthy or corporate elite. [46]

Cyberpunk stories have also been viewed as fictional foreshadowings of the Internet's evolution. The first descriptions of a worldwide communications network appeared long before the World Wide Web became widely known, albeit not before classic science-fiction writers like Arthur C. Clarke and some social observers like James Burke predicted that such networks would emerge. [47]

Anime and manga

The Japanese cyberpunk subgenre began in 1982 with the publication of Katsuhiro Otomo's manga series Akira, which was later popularised by a 1988 anime film version directed by Otomo. Akira influenced a slew of Japanese cyberpunk works, including Ghost in the Shell, Battle Angel Alita, Cowboy Bebop, and Serial Experiments Lain, among others. [66] The 1982 film Burst City, the 1985 original video animation Megazone 23, and the 1989 film Tetsuo: The Iron Man are examples of early Japanese cyberpunk works.

Unlike Western cyberpunk, which has its roots in New Wave science fiction literature, Japanese cyberpunk has its roots in underground music culture, notably the Japanese punk subculture that emerged from the 1970s Japanese punk music scene. With the punk films Panic High School (1978) and Crazy Thunder Road (1980), both portraying the disobedience and anarchy associated with punk, and the latter featuring a punk biker gang style, filmmaker Sogo Ishii introduced this subculture to Japanese cinema. Ishii's punk movies prepared the stage for Akira, Otomo's landmark cyberpunk picture. [67]

In anime and manga, cyberpunk elements are prevalent. Cyberpunk has been acknowledged and its influence is ubiquitous in Japan, where cosplay is popular and not only teens display such dress styles. Although Gibson did not know the location of Chiba at the time of writing the novel, and had no clue how perfectly it matched his vision in certain aspects, William Gibson's Neuromancer, whose impact dominated the early cyberpunk movement, was also situated in Chiba, one of Japan's greatest industrial districts. Because of the 1980s exposure to cyberpunk ideas and stories, it has been able to penetrate into Japanese culture.

Comics

In 1975, Moebius collaborated on a novella called The Long Tomorrow with writer Dan O'Bannon, which was published in the French magazine Métal Hurlant. It merged inspirations from cinema noir and hardboiled crime fiction with a distant sci-fi milieu, making it one of the first works to feature aspects today viewed as exemplifying cyberpunk. [88] In his 1984 novel Neuromancer, author William Gibson remarked that Moebius' artwork for the series, as well as other graphics from Métal Hurlant, had a big influence on him. [89] The series had a significant influence on the cyberpunk genre, being recognised as a source of inspiration for Ridley Scott's Alien (1979) and Blade Runner (1982). [91] The Incal, a graphic novel collaboration with Alejandro Jodorowsky released from 1980 to 1988, based on Moebius' aesthetic from The Long Tomorrow. The plot revolves around the adventures of a detective named John Difool in various science fiction settings, and while it is not limited to cyberpunk clichés, it does contain many of them. [92]

From 1983 to 1984, DC Comics released Frank Miller's six-issue miniseries Rnin with a slew of other seminal cyberpunk novels. The series is set in a dystopian near-future New York and incorporates elements of Samurai culture, martial arts flicks, and manga. It investigates the connection between an old Japanese samurai and the post-apocalyptic, collapsing cityscape in which he finds himself. The comic is also very comparable to Akira,[93], with incredibly powerful telepaths playing prominent roles and several significant graphics in common. [94]

Games

There are a lot of cyberpunk video games out there. Final Fantasy VII and its spin-offs and remakes, the Megami Tensei series, Kojima's Snatcher and Metal Gear series, Deus Ex, Syndicate, and System Shock and its sequel are all popular series. Other games are based on genre films or role-playing games, such as Blade Runner, Ghost in the Shell, and the Matrix trilogy (for instance the various Shadowrun games).

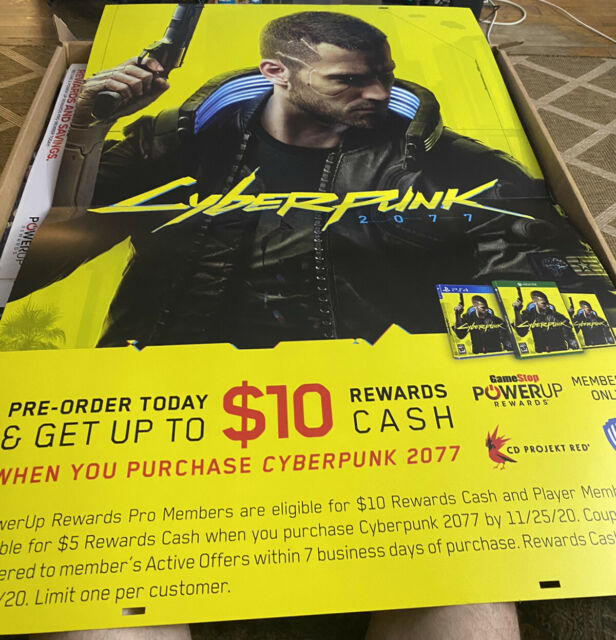

There are several RPGs with the name Cyberpunk: R. Talsorian Games' Cyberpunk, Cyberpunk 2020, Cyberpunk 2077, and Cyberpunk v3, and Steve Jackson Games' GURPS Cyberpunk, a GURPS module. Unlike FASA's approach to generating the transgenre Shadowrun game and its multiple sequels, Cyberpunk 2020 was built with the settings of William Gibson's books in mind, and to some extent with his consent. Both are set in the near future, in a world dominated by cybernetics. In addition, Iron Crown Enterprises published Cyberspace, an RPG that was out of print for some years before being re-released in online PDF form lately. Cyberpunk 2077, a cyberpunk open world first-person shooter/role-playing computer game, was released by CD Projekt Red (RPG)

On December 10, 2020, based on the tabletop RPG Cyberpunk 2020. [102] [103] [104] The US Secret Service invaded Steve Jackson Games' offices in 1990, confiscating all of their computers in a collision of cyberpunk art and reality. Officials denied that the GURPS Cyberpunk sourcebook was the intended objective, but Jackson would later write that he and his colleagues "were never able to secure the whole manuscript's return; [...] From March 4 to March 26, the Secret Service absolutely refused to return anything – then agreed to let us copy files, but only allowed us to copy one set of out-of-date files when we arrived at their office – then promised to make copies for us, but said "tomorrow" every day from March 4 to March 26. We received a set on March 26.

Social impact

Art and architecture

The cafes, brand-name businesses, and video arcades of the Sony Center on Berlin's Potsdamer Platz public plaza are described by writers David Suzuki and Holly Dressel as "a vision of a cyberpunk, corporate urban future." [111]

Society and counterculture

Cyberpunk fiction has influenced a number of subcultures. The cyberdelic counterculture of the late 1980s and early 1990s is one example. Cyberdelic, whose followers referred to themselves as "cyberpunks," aimed to combine psychedelic art and drug culture with cyberculture's technology. Timothy Leary, Mark Frauenfelder, and R. U. Sirius were among the first followers. Following the dot-com bubble burst in 2000, the movement basically died off.

Cybergoth is a fashion and dance subculture that relies on cyberpunk fiction as well as rave and Gothic subcultures for inspiration. In addition, in recent years, a distinct cyberpunk fashion has emerged[when? ] which rejects cybergoth's raver and goth elements in favour of urban street fashion, "post apocalyptic," utilitarian apparel, high-tech sportswear, tactical uniforms, and multifunctionality. "Tech clothing," "goth ninja," and "tech ninja" are all terms used to describe this style.

Related genres

New subgenres of science fiction evolved when a wider range of writers began to work with cyberpunk notions, some of which could be regarded ripoffs of the cyberpunk name, while others may be considered valid forays into newer ground. In various ways, these focused on technology and its societal impacts. "Steampunk," for example, is a subgenre set in an alternate history Victorian age that combines antiquated technology with cyberpunk's dismal film noir world view. The word was first used as a joke to characterise some of Tim Powers', James P. Blaylock's, and K.W. Jeter's novels in 1987, but by the time Gibson and Sterling entered the subgenre with their collaboration work The Difference Engine, it was being used seriously.[113]

Another early 1990s subgenre is "biopunk," a derivative style based on biology rather than informational technology (cyberpunk themes dominated by biotechnology). People are transformed in these stories, although not by mechanical means, but by genetic manipulation.

Postmodern literature has been described as a good fit for cyberpunk writings.[114]

Post a Comment